An Indigenous-led exhibition and publication project at the CCA

ᐊᖏᕐᕋᒧᑦ / Ruovttu Guvlui / Towards Home / Towards Home

Canadian Center for Architecture

Montreal Canada

Open until February 12, 2023

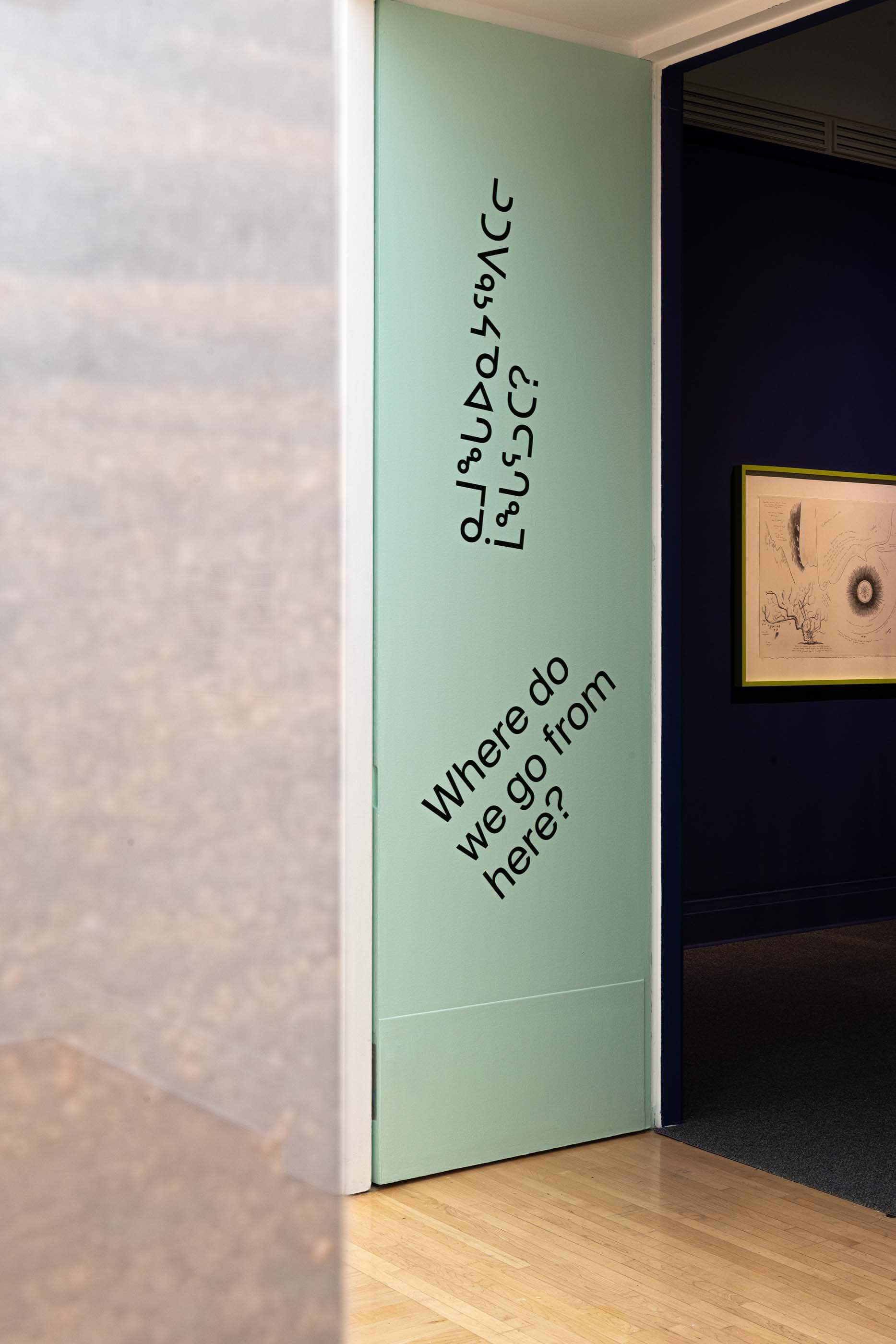

Visitors from ᐊᖏᕐᕋᒧᑦ / Ruovttu Guvlui / Towards Home / Towards Home are welcomed by the porch, a wooden structure that displays everyday objects of Arctic indigenous peoples, including a kerosene lantern, backpacks, clothing and a freezer. For Inuit and Sami members of Towards the housefrom the curatorial team, it evokes a unique blend of comforting scents – from motor oil, animal hides and other sources – unique to Nordic life. Beyond its manifestation of Arctic material culture, the porch is a declaratory statement welcoming Indigenous visitors to the museum, a space notorious for not valuing their views or presence. Designed by Taqralik Partridge and Tiffany Shaw, it marks the entrance to this Partridge terms a “space different from what [visitors] would expect from a building that looks like the CCA.

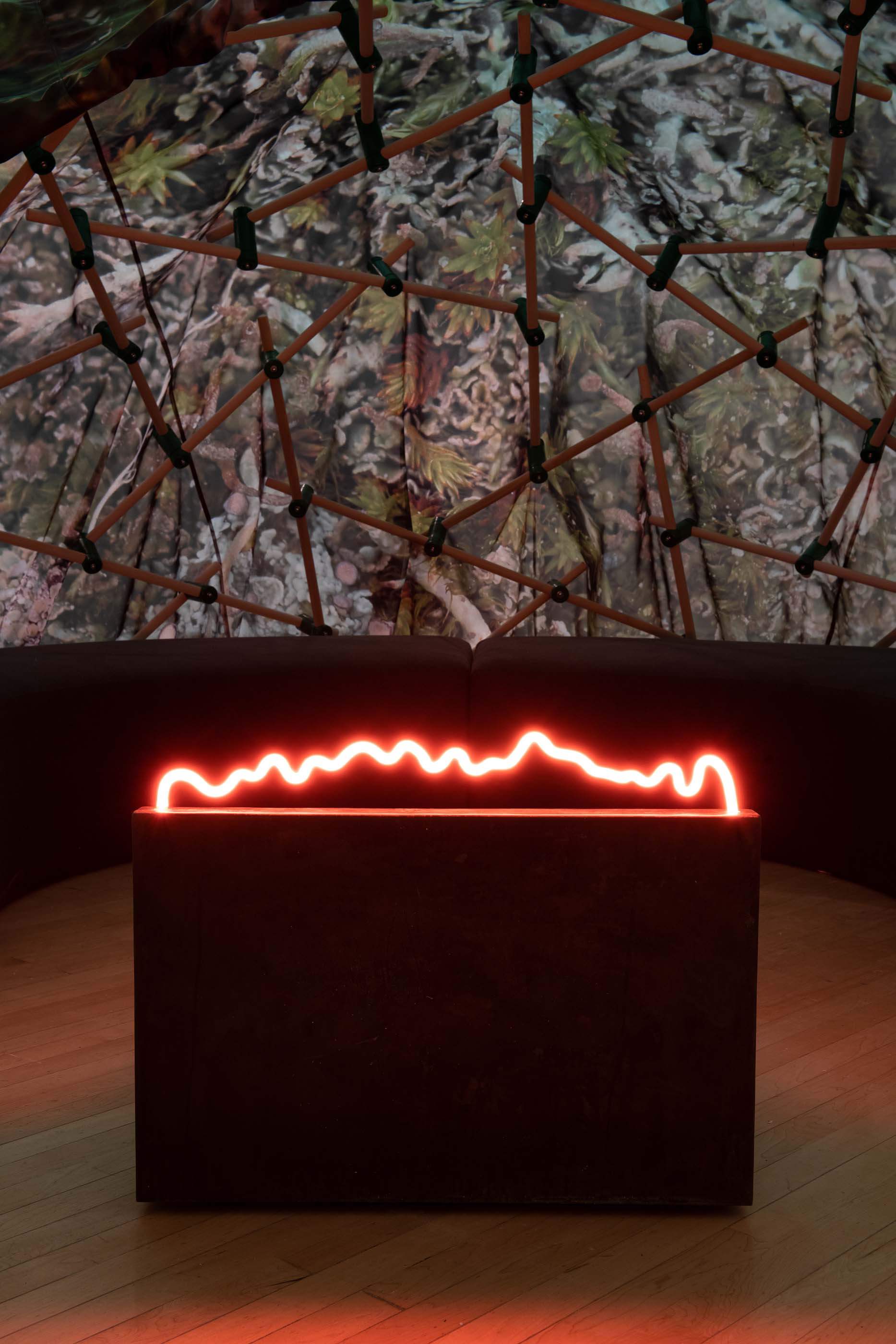

Organized by Partridge, Joar Nango, Jocelyn Piirainen and Rafico Ruiz, and designed by Shaw, Towards the house emerged from a collaborative process through which the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA) sought to explore how “Inuit, Sami and other Arctic communities create self-determined spaces”. Rather than simply documenting such spaces, Towards the house seeks to extend these manifestations of indigenous autonomy from the North to the museum of the South. The exhibition, whose title and wall text are rendered in Inuktitut, Sami, French and English (like the exhibition title above), features a series of six installations commissioned by six Indigenous artists, each seeking their own answer to questions asked by the commissioners: “Where is the house?” “Where do we go from here?” And: “Where does the earth begin?”

I call home by Geronimo Inutiq presents a matchbox house animated with childhood photographs and a radio broadcasting a virtual program specially commissioned for the exhibition. Radio is central to Inutiq’s sense of place as it connects Inuit near and far. The installation invites visitors to reflect not only on the flourishing of languages (her mother was one of the first radio hosts to broadcast in Inuktitut), but also to question the role of technology in societies. indigenous. Industrial technology facilitated colonialism and an extractive relationship with northern landscapes. But an innovative, flexible and finely tuned connection to technology such as radio also shapes Inuit and Sámi culture and provides the form and content of Inutiq’s work.

To make room is a recorded conversation between Partridge and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory. Each is shown life-size on a separate projection screen, an empathetic witness to the other’s testimony. Partridge notes that as Inuit, she and Laakkuluk live within institutional structures (such as Canada’s health, justice, and housing systems) without being part of them. Their powerful screen presences invite visitors into the spaces of their monologues, which address the housing crisis in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Together they poignantly describe Aanersaq, a strip of land in central Iqaluit where many homeless Inuit seek refuge, as “an oasis for Inuit who have nowhere to go”.

In recent years, Canadian society has been concerned about efforts to reconcile the Canadian state, with its majority population of settlers and immigrants, and the indigenous inhabitants of its territory. These efforts have been marked by heartfelt if sometimes meaningless gestures, hampered by awkwardness and hampered by an adamant refusal to reinvent the Canadian constitutional order along new lines. Recent discoveries of mass graves at many sites of former residential schools (to which an estimated 150,000 Aboriginal children were forcibly sent between 1831 and 1996) have only added to the sense that a much-needed wake-up call with Canada’s colonial past can no longer be delayed.

Since the 1960s, the Canadian state has become more representative of its changing population through successive bilingual and multicultural impulses. Reconciliation with the original peoples of Canada calls for something else, namely a dialectical process balancing pluralistic universalism and Indigenous sovereignty, all under the shadow of growing global ethno-nationalist tendencies. The movement for Indigenous self-determination is challenging Canada’s economic dependence on resource extraction, a reality whose legacy of environmental disasters was the subject of the CCA exhibit Everything happens so fast (timed to coincide with Canada’s 150th birthday in 2017). Nango himself notes how today’s “green” economies are frequently in conflict with indigenous land practices; it was explored by Sami artists at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale.

Museums have been at the forefront of the reassessment of Canadian history and culture and have often become flashpoints in this process. In 2015, less than four percent of arts professionals in major Canadian museums were Aboriginal. Recent efforts to transform Canadian museum space include the powerful National Gallery of Canada project In badakone | Continuous fire | continuous fire exhibition (2019) and the 2021 opening of Qaumajuq at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Designed by Michael Maltzan Architecture with Cibinel Architecture, the latter showcases Inuit art, providing a much-needed bridge between northern cultures and southern institutions.

In Montreal, the CCA has initiated a process to “facilitate [its] long journey towards fostering positive relationships with Indigenous and other peoples across Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montreal. To do this, the CCA seeks to “unlearn” the institutional practices it has used since its opening in 1989. New Scholarships for Indigenous designers and scholars are at the heart of these efforts, which aim to open up the institution in support of their voices.

Faced with this relevant but constraining Canadian context – which threatened to subsume all nuanced notions of “home” – the commissioners chose to set aside the colonial geography of colonizing nation-states in favor of a trans-Arctic approach. What unites the Inuit, Sami and other indigenous peoples of the Arctic? Certainly, a spirit of anti-assimilationist resistance and a desire to claim their rights to their lands and traditional ways of life. Likewise, their shared climate and landscape suggest the existence of what Ruiz calls a “Global North,” which spawned related cultural approaches to inhabiting the Arctic.

Conservatives have worked to proclaim a more universal – and perhaps geographically transferable – bond between their peoples through a common attitude toward inhabiting the land, an attitude that predates and exists outside of late capitalism. This common attitude based on oral tradition and lived experience in the Global North is what Towards the housecurators wish to share with its southern audience. Like Nango notes in conversation with Ruiz, “There are certain practices that every human being could incorporate more into their way of life and their way of seeing the world. Listening, for example, is one of them, challenging this constant need to always have control over processes, economy and resource flows. »

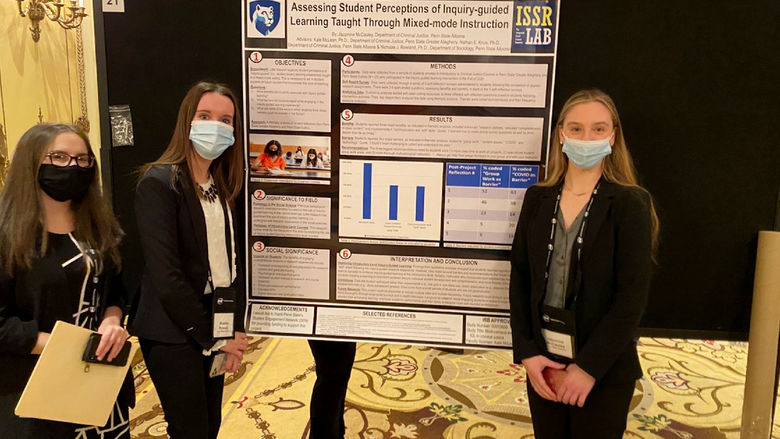

The Sámi Architectural Library of Nango (2018), was recreated in Towards the housethe last gallery. As an architecture student years earlier in Oslo, Nango was irritated by the lack of Sami culture in his curriculum and the scarcity of materials with which to fix it. His vision of a nomadic library, which could (at least in theory) travel between communities by sled, was born out of this lack. Visitors from Towards the house are expressly invited to sit and read in the library’s print collection. Nango’s design puts photocopies and brochures on a par with glossy hardbacks. For him, the library is an example of a place where Sami and Indigenous peoples can escape the “strangling and controlling power structures that capitalist nation states create when working with architecture”.

If the Partridge Porch makes a statement for Indigenous presence within the museum, the Nango Library exemplifies the struggle to have Indigenous knowledge taken seriously within colonial institutions like the CCA. Together, the facilities that make up Towards the house suggest a way forward for Indigenous leadership in the collective effort to create knowledge. As Partridge asserts in an interview with Ruiz and Elle den Elzenit is “essential that Inuit and Indigenous ideas about our future be privileged, because we are not leaving”.

Peter Sealy is an architectural historian and assistant professor at the University of Toronto.