New Getty Publication on Anatomical Illustration Explores Convergence of Art and Science

Exhibits of anatomical illustrations are like decks of cards: you can shuffle the deck but eventually the same old faces (or skulls, or spleens) appear. This is to the credit of Monique Kornell, the curator of the exhibition Flesh and Bone: The Art of Anatomy at the Getty Center and lead author of the accompanying publication, which she found trumps.

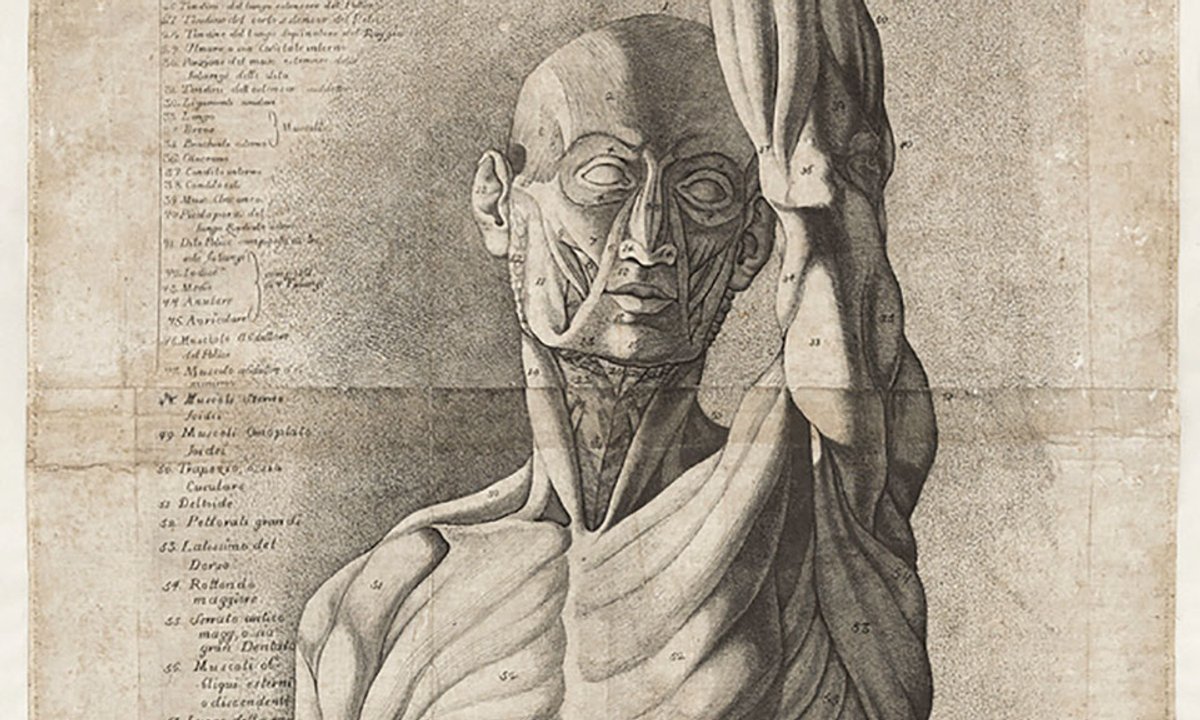

Among them are three striking life-size intaglio prints of flayed human bodies acquired by the Getty Research Institute in 2014. The work of Italian engraver Antonio Cattani, dating from around 1780, they depict two wooden caryatids carved by Ercole Lelli in the 1980s. 1730 for the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio in Bologna, and a wax composite écorché on a real human skeleton made by Lelli and Giovanni Manzolini for the Istituto delle Scienze in Bologna.

Here, Kornell and her co-contributors, Thisbe Gensler, Naoko Takahatake and Erin Travers, skillfully anatomize these extraordinary works, paying painstaking attention to their immediate production and situating them within a long-lasting landscape that spans five centuries. Cattani’s print policy is highlighted, including new details on subscription notices issued by Cattani and its partner. These illustrate two points that are relevant to many of the works presented in the publication.

First, they show the precarious economy of production and the balance to be struck between creating elaborate pieces intended to be enjoyed by wealthy collectors or sold as practical aids to impoverished artists or medical students. Second, they expose the importance of attribution and the relative weight given to the artist and the anatomist according to the public. Thus, the fashionable name of Lelli features prominently in Cattani’s prints, while the names of Manzolini and his partner in life and work, Anna Morandi, are absent.

The shadowy boundaries between living and dead, anatomist and artist, past and present are recurring themes in this publication.

The nuanced boundaries between living and dead, anatomist and artist, past and present are recurring themes in this publication. In eight short essays (six by Kornell, one by Gensler and one by Travers) and a co-authored text for the 56 exhibitions, it deals with subjects such as the vivid arrangement of figures in early treatises on modern anatomy – always walk, without skin, in the Arcadian fields, the surprising passers-by and the contrast of scale between the spectacular and the everyday.

A particular delicacy is that of John Walker Artist’s Pocket Companion (1787), which is easily designed to make the budding Royal Academician disappear from view whenever Sir Joshua Reynolds – the President of the Academy and no fan of the gruesome minutiae of anatomical detail – staggers. It also highlights the constant reworking of bodies to manufacture reputation as well as knowledge, such as with the limbless marble torsos of antiquity, redesigned with added viscera for the self-proclaimed anatomist, Andreas Vesalius (1514-64) , then reposted with an update. livers-and-lights by many of his successors.

Concept artist Tavares Strachan Robert (2018), a science-based work, featuring purple and blue neon lights, Pyrex, transformers and a medium-density cardboard box Artist collection

Along with a solid, albeit familiar, selection of primarily print books, Kornell introduces a few wildcards. Among them, that of Robert Rauschenberg Booster (1967), a “life-size self-portrait of [his] inner man”, as the artist described it, which in its composite complexity echoes the prints of Cattani. Even more striking is the neon sculpture by Tavares Strachan Robert (2018), part of a series of works celebrating African-American astronaut Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. It is included here without the neon script in which Strachan (b. 1979) confronts the racism that surrounded Lawrence before and after his death. in 1967. As Gensler notes, the power of Strachan’s work comes from appropriating the visual language of anatomical illustration to defy erasure from those who provided his subjects. If there is a reproach to be made with this publication – and the virtues are multiple – it is that, in the praise of the anatomists and the artists with whom they worked, the authors too quickly take at face value the credit that ‘they cut into the bodies of others.

• Monique Kornell, with contributions from Thisbe Gensler, Naoko Takahatake and Erin Travers, Flesh and Bone: The Art of AnatomyGetty Research Institute, 249pp, 163 color illustrations, $50/£40 (hb), published March 1, 2022

• Flesh and Bone: The Art of AnatomyGetty Center, Los Angeles, through July 10, 2022

•Simon Chaplin is managing director of the Arcadia charity fund, former director of culture and society at Wellcome and director of museums and special collections at the Royal College of Surgeons of England