New Publication Brings Ravishing Life To Norway’s Medieval Wooden Church – A Story Of The Art Of Sleeping Beauty

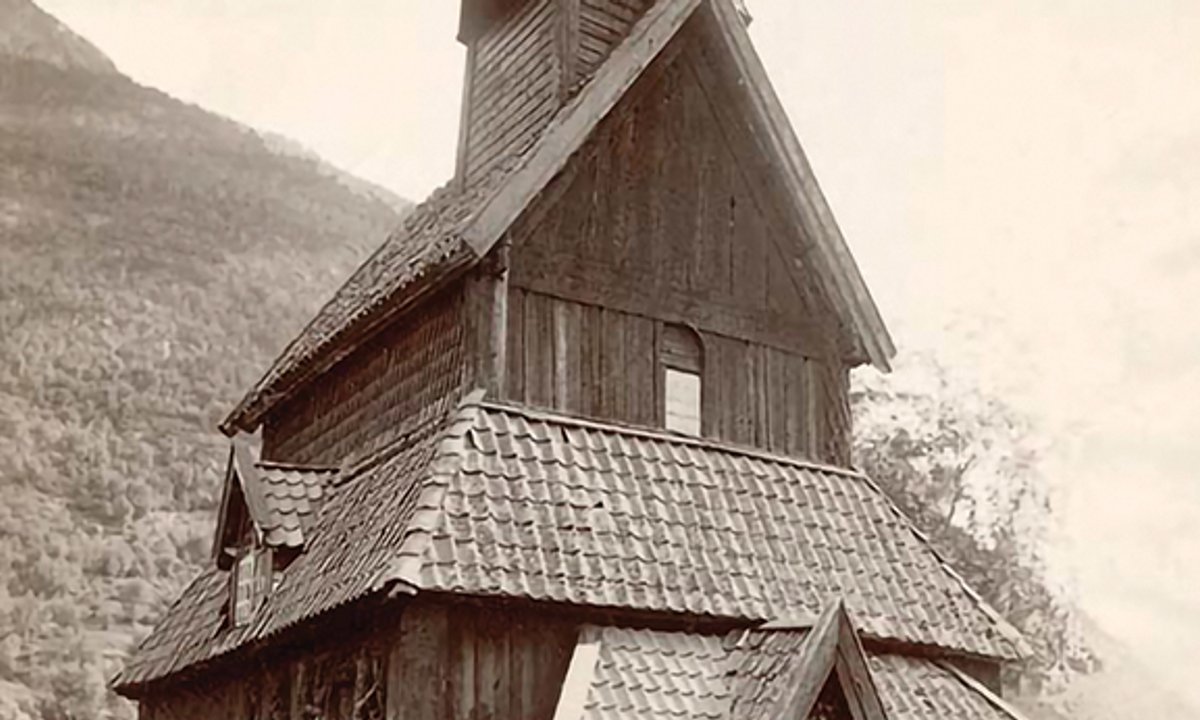

The medieval wooden ‘moat’ church at Urnes near the Sognefjord in western Norway is one of the most fascinating Sleeping Beauties in art history. Despite all that it enjoys Unesco World Heritage status, gave its name to an artistic style and is arguably both the largest and most haunting of Norway’s less than 30 surviving churches, it can only be a distinct selection, a few non-Scandinavians who have already made the pilgrimage to see it – until recently the easiest way to get there was by boat.

Fortunately, the extensive illustrations in this new book are the next best thing, as they combine exemplary detailed photography with evocative views of its setting: in one particularly memorable case against a wintry backdrop of the fjord and snow-capped hills beyond.

Interior from the west Siri Uldal

What makes Urnes so special? In the end, and despite the undoubted architectural merits of the building itself and the fascinating carved capitals of the nave and other elements of its interior, it is the extraordinary fantasy and refinement of the sculptures that we find now on the north outer wall. Curiously, they originally adorned the west front of a previous church on the site and were obviously lovingly preserved when it was replaced.

Almost inevitably, a detail of this decoration graces the cover of James Graham-Campbell’s viking art in Thames & Hudson’s valuable World of Art series, a volume first published in 2013 and most recently in a new edition in 2021. If I point out that Graham-Campbell refers to these sculptures as having belonged to the second of two previous churches on the site, but the present volume clearly indicates that they actually belonged to the third of a total of four churches, the intention is simply to underline the fundamental importance of this new book by providing all the up-to-date information on the history of this extraordinary ensemble. Additionally, as explained in the book’s introduction, the research is “deliberately published in English to reach a wide audience.”

The book comes directly from a seminar organized at Urnes itself in September 2018, which brought together ten archaeologists and art historians, not only from Norway but also from France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United States. Their approaches prove to have been refreshingly diverse and comprehensive, but it was not necessary to force the book to be divided into three coherent parts: situating Urnes, the 11th century church and the church of the twelfth century.

Overall, this structure involves starting with the background of the building itself before moving on to how it connects with surprisingly distant monuments and artifacts. This overview explains both the inclusion of the word “global” in the title of the book, as well as individual chapter headings such as “The European Significance of Urnes: An Insular Perspective on Urnes and the Urnes Style” by Griffin Murray and “Norse Encounters with the Mediterranean and Near Eastern Worlds in Urnes Capitals”.

The solid basis for any more speculative research to be found in the various contributions is a reliable dendrochronology for Norway of those centuries. As a result, it was possible to establish that the trees used for Urnes III were felled in the winter of 1069-70 and pruned immediately afterwards. At the same time, Urnes IV can now be confidently dated to 1131-1132, an account three decades earlier than hitherto assumed based on stylistic analysis. Poignantly, this new evidence means that Urnes III only existed for sixty years. Given the antiquity of the church and its furnishings, this provides a remarkable degree of certainty regarding dating and is likely linked to the understanding of a vast range of other monuments and sculptures.

In the best sense, this exemplary book is not the last word on Urnes Stave Church, not least because its authors at least occasionally disagree with each other, meaning that one either the other – or perhaps both – must be wrong. To give an example, on page 414 the barefoot cleric on one of the capitals is cautiously identified as a Canon Regular, while on page 419 he is confidently described as a Bishop, while the plate 85 is noncommittally captioned as showing a “clerk with crosier”. More generally, and especially in the light of the ambition of the work to include Urnes in a global context, it is by no means excluded that specialists in other fields now see in it hitherto unsuspected links with the rest of the world.

Kirk Ambrose, Margarete Syrstad Andås and Griffin Murray (eds.), Urnes Stave Church and its Worldwide Romanesque ConnectionsBrepols, 480pp, 230 color & 7 b/w illustrations, €165 (hb), published May 13

• David Ekserdjian is Professor of Art and Film History at the University of Leicester